Four Lessons (re)Learned from Speaking at TEDx (Facilitation Friday #17)

How can you bring your authentic self and a facilitative approach when you're set up to be the "sage on the stage"?

Given the amount of public speaking I’ve done, I wasn’t overly concerned about appearing onstage to talk about lifelong learning at TEDx Indianapolis. But I typically facilitate half-day or full-day workshops or present 60-minute keynotes, not a 10-minute presentation (my TEDx talk). And while some of what I’ve gleaned presenting 5-minute IGNITE talks (on innovation and on personal priorities/saying yes less) applied to TEDx, I learned (and relearned) a few important lessons about public speaking.

Edit ruthlessly.

Editing can help turn writing from good to great. My undergraduate academic work as an English major instilled this mindset. Writing for journals and trade publications throughout my career has reinforced it.

My initial TEDx presentation drafts covered many more themes and examples than the final version. Even it may have tried to do too much given the time constraints. If you want to see how the content transforms with more time, here is the 25-minute “HEd Talk” version I later did at a higher education association conference. I subsequently developed a 50-minute keynote and a 90-minute workshop amplifying the same content.

My editing process consisted of asking myself four questions repeatedly:

What do I most want people to think about and act on?

Why is this point (this example) important to include?

If I eliminate ____ from the talk, will it reduce the overall impact? If so, how much?*

Is there a better way to show rather than tell the point I am trying to make?

* This is a variation on a principle I once heard the celebrated graphic designer Chip Kidd espouse for working on book covers. He said that he would continue to eliminate individual elements from a draft cover design until he reached a point where taking one more would cause the design to collapse (think pulling out blocks in Jenga).

Leverage metaphors, analogies, and stories.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, a powerful metaphor or analogy in a presentation allows you to use minimal verbiage to convey maximum meaning. Similarly, a carefully crafted story can efficiently engage participants’ attention and energy, enhance their retention of your key points, and often inspire action. Always proof your draft content for opportunities to replace lengthy commentary with a metaphor, analogy, or short story.

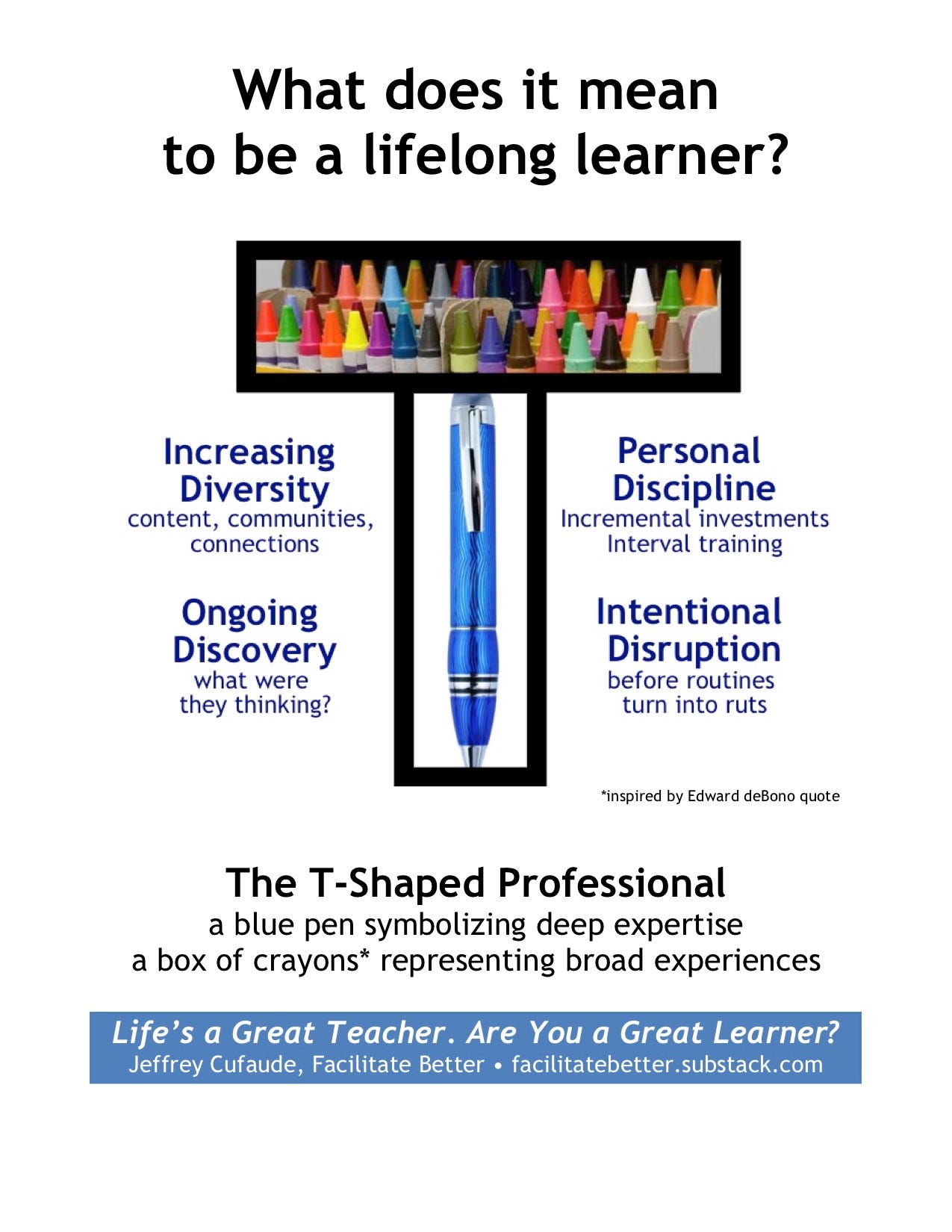

Scanning what attendees amplify in their social media posts allows us to gather evidence on well we leverage metaphors, analogies, and tools. For my talk, some mentioned the Edward deBono crayon and blue pen image and quote, some spoke about a bagged lettuce example I used, while others noted my Sondheim and George Seurat references. I had chosen each of these metaphors or stories as potentially memorable anchors to encapsulate my major points.

Honor your voice.

My work is almost always experiential and interactive: it's what I am known for contributing. But I initially told myself it was not possible to do that in a 10-minute stage presentation with 500 people in a fixed-seating auditorium. My first presentation design included nothing of the sort and I hated it. It felt flat. Worse yet, it didn’t feel like me and I knew I wouldn’t enjoy doing it.

Talking with a few colleagues helped me see how to bring more of who I am and my professional core values into the presentation. This resulted in the silent opening with me surreptitiously displaying slides that revealed thought bubbles (often humorous) of what I presumed audience members were thinking as I stood alone on that large stage, staring at them but saying and doing nothing.

It was perhaps the most terrifying 40 seconds I’ve ever had speaking in public. But it achieved my primary objective: turning passive spectators into somewhat engaged learners while illustrating the main theme of my talk. It was counterintuitive and somewhat risky, but thankfully, it worked pretty well.

Prepare your way.

In talking with the other speakers, I was fascinated by our varied preparation approaches: writing it out almost verbatim, using a lengthy slide deck to tell the story, practicing in front of family and friends. Everyone found a way that worked for them.

My prep was somewhat different. The first and only time I went through the entire talk was the day I actually delivered it at the conference. Being present is a key part of my commitment as a facilitator, and as a speaker, I didn’t want to be so scripted and polished that the talk could seem as it if was delivered on autopilot.

Instead, my rehearsal consisted of crafting the language around what I labeled “set pieces,” the key verbiage for each major point. I then ran through those enough times to get a feel for the words and the rhythm that mattered most, but never full scripted or memorized them. I wanted the transitions between—and the connections among—to emerge in the moment on stage.

I hadn’t really been too concerned about this slightly unorthodox approach until I received this text from a friend a few days before the event: How goes getting ready for what might be the most important 600 seconds of your entire professional career? (Note to self: get new friends. LOL).

My friend was joking, of course. It’s not like I was speaking on the mainstage at the TED Conference (um, Chris Anderson, I’m available though).

And I’ve long believed that what a speaker should fear most is the absence of any nervousness or performance anxiety when taking the stage. The moment we think we have it all figured out, believing nothing can go wrong, is often the moment when things unravels. This is as true for speaking on a stage as it is interacting with a friend or colleague. You can't rehearse authenticity.

Bottom Line?

Share your story.

Engage on your terms.

Prepare as you see fit.

Ultimately, what others make of it is beyond our control.

And this is perhaps the most important lesson I hope never to forget.

Getting in Action

If you were to deliver a short speech, what elements of your authentic self would you most hope to incorporate? How might you do so?

To better facilitate understanding, retention and recall, and action, what are some metaphors, analogies, or stories you could use in meetings or workshops you facilitate?

What does “prepare your way” look like for your speaking and facilitation efforts? How might you codify your process (if you haven’t already) so that you can easily use it whenever needed?

© Facilitate Better and Jeffrey Cufaude. All rights reserved.

To affordably license this content for reprint on your site or in electronic or print communications or to contact me regarding customized facilitation skills workshops or consultations, complete this form.